Produced by REFSA

Read #ProjekMuhibah Strategy 2 and Strategy 3 HERE

To download PDF version, please click here.

For Mandarin version, please click here.

For Bahasa Malaysia version, please click here.

Months of brute lockdowns and little optimism on Covid-19 test positivity rates have justified calls for a shift in our pandemic management and economic recovery strategy. As part of a comprehensive proposal under #ProjekMuhibah, we propose a gradual reopening of businesses using science-based approaches as well as to push for more fiscal injections and enhanced social protection for Malaysians.

Indeed, as vaccination rates surge, some industries are beginning to see the light at the end of the tunnel, but for many others, recovery still remains elusive. This summary aims to illustrate the economic impacts experienced by several industries as well as some limitations of current policies.

Retail

Arbitrary distinctions between “essential” and “non-essential” sectors is hurting the Malaysian economy further. Essential sectors could be a hotbed for high-risk transmission, while other non-essential sectors have seen a gradual decline in their rate of transmission, especially for those following strict SOPs. For example, the retail sector saw its worst performance (-16.3% in 2020) since the Asian Financial Crisis in 1998 (-20.0%)[1] with the fashion/apparel sub-sector registering the worst decline (-49.6% in Q4 2020), followed by department stores (-44.7%). Due to travel restrictions (including domestic tourism) and work-from-home adoption, reduced shopping traffic has caused 30% of malls to close since March 2020, leaving approximately 300,000 personnel jobless[2]. Prolonged retail closures will exacerbate fractures in the market as international brands and investors may exit, which will lower spending and consumption even further. Numerous local businesses have ceased operations as well, quashing the entrepreneurial scene in Malaysia. What frustrates retail operators most is that the restrictions inhibiting their operations do not seem to be on the basis of science and data.

Essential sectors could be a hotbed for high-risk transmission, while other non-essential sectors have seen a gradual decline in their rate of transmission, especially for those following strict SOPs. For example, the retail sector saw its worst performance (-16.3% in 2020) since the Asian Financial Crisis in 1998 (-20.0%)[1] with the fashion/apparel sub-sector registering the worst decline (-49.6% in Q4 2020), followed by department stores (-44.7%). Due to travel restrictions (including domestic tourism) and work-from-home adoption, reduced shopping traffic has caused 30% of malls to close since March 2020, leaving approximately 300,000 personnel jobless[2]. Prolonged retail closures will exacerbate fractures in the market as international brands and investors may exit, which will lower spending and consumption even further. Numerous local businesses have ceased operations as well, quashing the entrepreneurial scene in Malaysia. What frustrates retail operators most is that the restrictions inhibiting their operations do not seem to be on the basis of science and data.

Prior to MCO 3.0, health ministry data showed that cases linked to malls made up only 0.8% of all cases in May. Mall operators credited this to stricter SOPs including a maximum visiting time of 2 hours. Tough times have also pushed retailers to offer innovative initiatives like curbside pickups, buy-online-pickup-in-store (BOPIS) and self-checkouts. The sector is actively improving on their SOPs and innovating methods to adapt. Hence, instead of closing all ‘non-essential’ retail or restricting them with baseless SOPs, authorities should carry out transmission risk assessments and allow low-risk retail outlets to operate, giving them a chance to earn for their survival.

Creative Industry

Another sector that has been paralysed by lockdowns is the creative industry (from visual arts to live performances). Most mediums of art function by connecting the audience to the artwork/artists in the same location – usually involving social interaction. For instance, exhibitions serve to connect artists and collectors; concerts bring together enthusiasts and performers. The cancellation and postponement of events have almost zeroed the incomes of the artists and venue providers. For evidence, the Malaysian Philharmonic Orchestra (MPO) is ‘re-evaluating its business model’ where most musicians’ contracts are left unrenewed[3][4]. The Kuala Lumpur Performing Arts Centre (KLPAC) is barely holding on, supported only by its community crowdfunding calls[5]. Many freelance artists also fall under the ‘gig-worker’ category and receive far less social protection from the government[6]. Previously, digital communication technology was explored by the industry to offer virtual showcases. But in the most recent restrictions, even filming and recording activities are disallowed until Phase 3 of the National Recovery Plan, pushing the industry to the brink. In the long run, insufficient jobs support and under-revised SOPs for the creative industry will set Malaysia’s artistic and cultural appreciation back years.

performances). Most mediums of art function by connecting the audience to the artwork/artists in the same location – usually involving social interaction. For instance, exhibitions serve to connect artists and collectors; concerts bring together enthusiasts and performers. The cancellation and postponement of events have almost zeroed the incomes of the artists and venue providers. For evidence, the Malaysian Philharmonic Orchestra (MPO) is ‘re-evaluating its business model’ where most musicians’ contracts are left unrenewed[3][4]. The Kuala Lumpur Performing Arts Centre (KLPAC) is barely holding on, supported only by its community crowdfunding calls[5]. Many freelance artists also fall under the ‘gig-worker’ category and receive far less social protection from the government[6]. Previously, digital communication technology was explored by the industry to offer virtual showcases. But in the most recent restrictions, even filming and recording activities are disallowed until Phase 3 of the National Recovery Plan, pushing the industry to the brink. In the long run, insufficient jobs support and under-revised SOPs for the creative industry will set Malaysia’s artistic and cultural appreciation back years.

Travel and Tourism

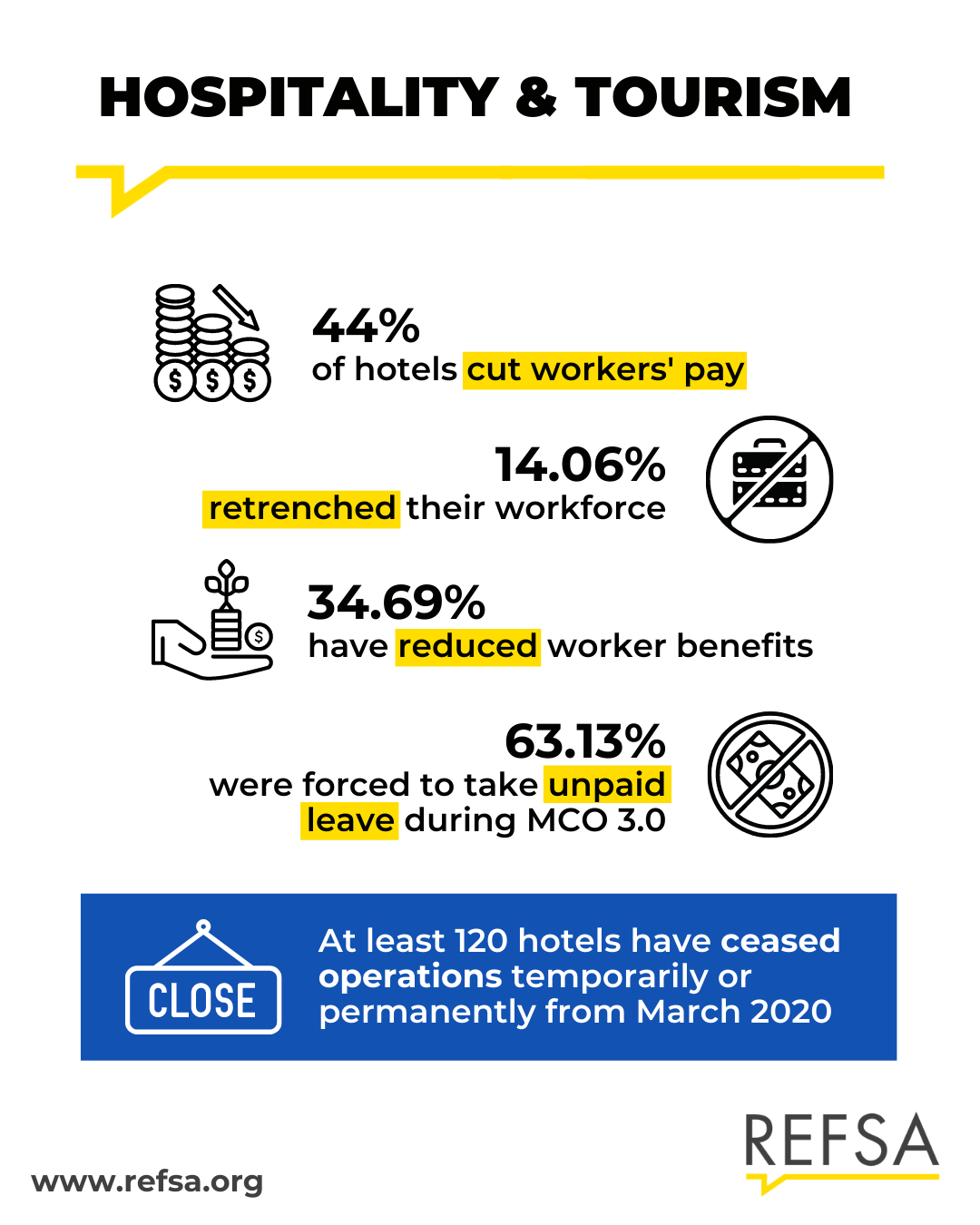

Unemployment is unfortunately but undoubtedly increasing in many industries, but weak demand due to restrictions has left the tourism and travel industry severely impacted. AirAsia has retrenched 2,400 employees and is flying only 8% of its Malaysian routes[7][8] whereas Malaysia Airlines has left over 13,000 employees on unpaid leave[9]. Malaysian Association of Hotels (MAH) have claimed that MCO 3.0 has left 61.13% of workers on unpaid leave. According to MAH, only 70% of hotels are still operational with average occupancy rates below 20%. Aviation has lost RM13 billion in 2020[10] while hotels have lost RM11.3 billion since 2020, without any clear signs of recovery.

Sports and Fitness

Although government stimulus packages have provided comprehensive coverage, it is still difficult to guarantee that no one is left out. One such ‘forgotten group’ is sports and fitness. According to a Star newspaper interview, Lim Chong Ghee of World Endurance Malaysia Sdn Bhd (organisers of Ironman Malaysia) said “We are one of the forgotten groups […] we tried to get financial aid […] but one or two voices are not heard […] we decided to form Sports Industry Coalition (SIC).” SIC noted that mega events and sports tourism, supported by inbound travellers, generated over RM1 billion in economic impact in 2019. But a recent survey reported that revenues have nose-dived by 99% and the workforce by 85%[11] since the pandemic.

that no one is left out. One such ‘forgotten group’ is sports and fitness. According to a Star newspaper interview, Lim Chong Ghee of World Endurance Malaysia Sdn Bhd (organisers of Ironman Malaysia) said “We are one of the forgotten groups […] we tried to get financial aid […] but one or two voices are not heard […] we decided to form Sports Industry Coalition (SIC).” SIC noted that mega events and sports tourism, supported by inbound travellers, generated over RM1 billion in economic impact in 2019. But a recent survey reported that revenues have nose-dived by 99% and the workforce by 85%[11] since the pandemic.

Agriculture and Fisheries

While the pandemic has induced change in consumer habits, we may not notice the severe disruption to supply chains. Zooming in on aquaculture and fisheries, low consumer demand due to dine-in restrictions and seafood restaurant closures have caused seafood prices to drop and stock pile-ups[12]. A study in April 2020 reported that the price of fish sold from fishermen to village middlemen has decreased by 50~70% than before the MCO (March 2020)[13]. Demand for higher-value fishes like groupers and Spanish mackerels – often enjoyed in restaurants and by tourists, are affected the most. With the income from fishing barely enough to cover the costs, Malaysia Inshore Fishermen Action Network (JARING) raised the concern that fishermen may not go out fishing anymore to avoid losses[13]. MIDA reported a 33.3% job loss in fisheries[14], impacting the lives of many fishermen who were already considered lower-income groups in the first place.

While the pandemic has induced change in consumer habits, we may not notice the severe disruption to supply chains. Zooming in on aquaculture and fisheries, low consumer demand due to dine-in restrictions and seafood restaurant closures have caused seafood prices to drop and stock pile-ups[12]. A study in April 2020 reported that the price of fish sold from fishermen to village middlemen has decreased by 50~70% than before the MCO (March 2020)[13]. Demand for higher-value fishes like groupers and Spanish mackerels – often enjoyed in restaurants and by tourists, are affected the most. With the income from fishing barely enough to cover the costs, Malaysia Inshore Fishermen Action Network (JARING) raised the concern that fishermen may not go out fishing anymore to avoid losses[13]. MIDA reported a 33.3% job loss in fisheries[14], impacting the lives of many fishermen who were already considered lower-income groups in the first place.

E-Commerce

In stark contrast, the e-commerce industry was among the few sectors that were able to capitalise on the pandemic. What used to be an alternative form of shopping suddenly became an essential service thanks to the pandemic[15]. According to GlobalData’s analysis, fear of virus infections through cash-handling and social interaction at physical stores propelled Malaysia’s e-commerce growth (24.7% growth in 2020)[16]. Clarence Leong of EasyParcel also pointed out the accelerated digitalisation in shopping, noting that before the pandemic, many consumers were not even familiar with QR codes. The industry grew so rapidly that it is now the source of new employment as freelance drivers/riders for those who lost their jobs.

pandemic. What used to be an alternative form of shopping suddenly became an essential service thanks to the pandemic[15]. According to GlobalData’s analysis, fear of virus infections through cash-handling and social interaction at physical stores propelled Malaysia’s e-commerce growth (24.7% growth in 2020)[16]. Clarence Leong of EasyParcel also pointed out the accelerated digitalisation in shopping, noting that before the pandemic, many consumers were not even familiar with QR codes. The industry grew so rapidly that it is now the source of new employment as freelance drivers/riders for those who lost their jobs.

Conclusion

The pandemic has inflicted uneven impacts on each industry, ranging from critical damage for many to positive growth for a select few. In many cases, one industry’s decline leads to ‘spillover effects’ that affect related, smaller-scaled businesses. As a quick example, cancelling live sports matches not only affects athletes, but the impact is propagated to media broadcasters, venue providers, merchandise and food vendors at stadiums…etc. As attention is usually fixated on the ‘main’ industries (in this case, sports), actual economic damages may be under-reported, causing the problem of unintentionally ‘leaving out’ certain parties when formulating aid programs.

The pandemic has inflicted uneven impacts on each industry, ranging from critical damage for many to positive growth for a select few. In many cases, one industry’s decline leads to ‘spillover effects’ that affect related, smaller-scaled businesses. As a quick example, cancelling live sports matches not only affects athletes, but the impact is propagated to media broadcasters, venue providers, merchandise and food vendors at stadiums…etc. As attention is usually fixated on the ‘main’ industries (in this case, sports), actual economic damages may be under-reported, causing the problem of unintentionally ‘leaving out’ certain parties when formulating aid programs.

The unfortunate reality is that challenges faced by many industries are largely caused by uncontrollable factors either due to the non-pandemic-friendly nature of their operations or the safety-driven shift in consumer habits. But what is controllable is the response from the government. In light of the examples provided above, instead of banking on lockdowns, the government should increase targeted assistance for the economy while strengthening SOPs using science-based approaches. The government should uphold its responsibility of supporting Malaysians instead of working against them by unnecessarily burdening businesses with arbitrary, baseless SOPs or providing inadequate support for overlooked industries.

| To read about our policy recommendations to better handle the health and economic crisis, check out #ProjekMuhibah :

Strategy 2 on reopening the economy gradually and responsibly. Strategy 3 on enhanced targeted assistance for employers and employees. |