By Raja Ahmad Iskandar Fareez and Morgan Loh

They called Covid-19 the great equaliser. The great leveler. Yet, it turns out that not everyone faces the same or equal hardship during the pandemic. Some, as the Orwelian saying goes, were more equal than others.

As Malaysia went into its first ever nationwide lockdown on 18 March 2020, two distinct lockdown realities emerged. One for the privileged – as many tried to cope with living in the new normal being cooped up in their own homes, they turned to popular ‘lockdown trends’ that were a craze at the time such as whipping up their own frothy Dalgona coffee, bingeing on the latest shows or their usual favourites on widely available streaming platforms, trying their hand at breadmaking, gardening, exercising, or reading, and the list goes on.

Concurrently, the less privileged had to endure a much harsher reality. Survival was and still is a daily struggle. They are often left in the lurch wondering when their next meal would be, and if they could manage to survive through the night. At times, they are at a loss as the government urges them to stay at home, yet they have no such place they can call home.

This disparity is not new. We have to recognise that the pandemic itself did not cause this inequality. But, it did widen the gap between the haves and have nots and further exposed the cracks in our system. This was further exacerbated by the then government’s response of implementing strict lockdown measures, hoping to rein in the Covid-19 outbreak. At the onset of the lockdown, the unemployment rate amongst heads of low-income households, was at roughly 25%, which was five times the national average (5.3%). For female heads of low-income households, the rate was higher at 32%. Indeed, Covid-19 was not a leveler.

Political survival trumping people’s well-being

While the health crisis continued to persist, the political turmoil in Malaysia has added insult to injury as social problems worsened. The then newly formed Perikatan Nasional administration which ascended to power via a political coup at the end of February 2020 only commanded a wafer-thin majority. It came as no surprise then that in its fixation to survive politically, it somehow neglected pursuing proactive data-backed measures to systematically address the surging cases of Covid-19. Instead, it fully relied on a disruptive strategy of perpetual lockdowns that crushed more lives and livelihoods than it did the virus.

Facing threats from its own fold, the then Prime Minister Muhyiddin Yassin resorted to calling for a national emergency which effectively suspended parliament for 7 months from January to July 2021 in hopes to stave off any attempts to remove him from office. Consequently, policymakers were denied the chance to formulate much needed policy responses to effectively address the wide-ranging impacts of the pandemic as well as keeping the government in check.

The lack of meaningful policy interventions led to worsening conditions. Since the pandemic began, more than half a million of Malaysian middle-income (M40) households earning income of between RM4,850 and RM10,959 have slipped into the bottom 40 percent (B40) income category. Meanwhile the absolute poverty figure shot up to 8.4% in 2020 from 5.6% in 2019 (pre-pandemic). Additionally, more than 10,000 individuals have been declared bankrupt during the lockdown period of March to July 2020 according to the Malaysian Department of Insolvency (MdI).

Taking matters into their own hands, kind-hearted and enterprising Malaysians banded together and initiated a crowdsourced aid distribution network dubbed the #KitaJagaKita (we take care of each other) Initiative in 2020 to match organisations with individuals who are in dire need of assistance and a separate #BenderaPutih (white flag) initiative in 2021 invoking the same community spirit to help lower income families signal distress and receive aid.

While these inspiring movements symbolise a sense of solidarity among the people, charitable acts alone are not sufficient nor are they sustainable to address the economic hardships faced by these vulnerable groups. More is needed to be done to ensure Malaysians do not fall through the cracks.

Given the systemic nature of these challenges, the state must play a role in addressing them. Amplified by the Covid-19 pandemic, Malaysians today experience the combined challenges of economic insecurity due to the destruction of jobs and the lack of social protection stemming from a fragmented system. If left unchecked, the chasm between these two Malaysian realities will only grow bigger. Thus, economic solidarity should be at the forefront of any government’s post-pandemic recovery agenda, paving the way for the nation to build back better.

The following sections delve deeper into these challenges and attempt to respond to them through a social democratic framework.

Saving jobs and livelihoods

Beyond being a means of survival, employment or jobs form an integral part of our modern identity. It gives us a sense of security, purpose and direction. Losing one’s job is akin to losing a part of oneself. As the pandemic stretched from weeks to months, safeguarding jobs must be the first line of defence in protecting Malaysians’ lives and livelihoods.

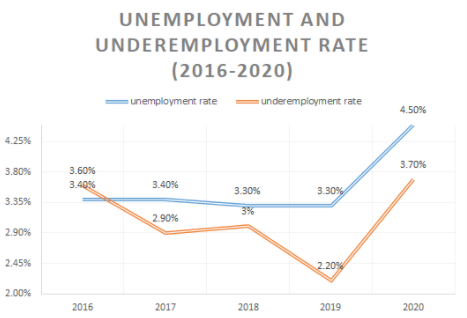

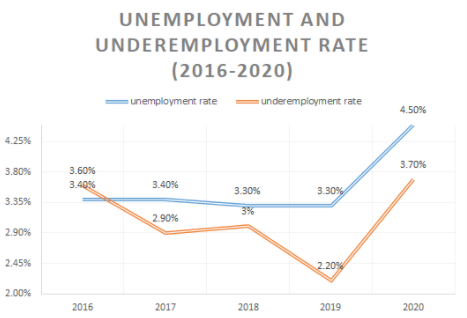

During the implementation of the nationwide lockdowns, both unemployment and underemployment rates reached record levels while approximately 768,700 Malaysians dropped out from the labour force. The reduction in work hours could signify that the lockdown has forced some full-time workers into part-time work, perhaps bringing home lower pay as well.

Graph 1 : Unemployment and Underemployment

Source: Department of Statistics Malaysia (2021). Unemployment is defined as individuals available for work and actively seeking employment. Underemployment rate refers to the rate of employed people working less than 30 hours.

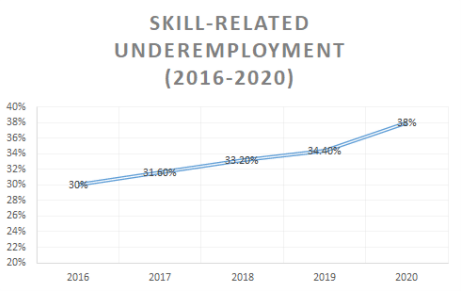

Graph 2: Skilled-Related Underemployment

Source: Department of Statistics Malaysia (2021)

Within the same time-frame, skill-related underemployment also increased by 18.9% indicating a job mismatch where individuals ended up accepting jobs with lower requirements than their educational attainment. While this was steadily increasing prior to the Covid-19 pandemic, the more significant rise in 2020 may be attributed to individuals who were forced to transition into the informal sector as they faced redundancies from their previous roles. This would be applicable to pilots, flight attendants, tourism, hospitality, and other workers in sectors severely affected by the pandemic and lockdowns who then decided to take up gig work as e-hailing or delivery riders or other segments of informal work.

The grim reality is that not everyone has the luxury to work from home. In fact, only 44% of Malaysian workers were working from home at the start of Malaysia’s nationwide lockdown. Meanwhile, only one in four self-employed individuals were able to choose to work from home. In contrast, daily wage workers in the services sector have no such option and short of any modified guidelines or arrangement allowing them to work safely during a pandemic, they had to abide by the ‘stay-at-home’ order without receiving any source of income.

At a time when the private sector is struggling to maintain their businesses due to severe disruptions, the government plays a vital intervening role to minimise job losses. To this extent, the Malaysian government introduced the Wage Subsidy Programme (WSP) via its various stimulus measures to eligible employers to retain their employees. Unfortunately, according to the Federation of Malaysian Manufacturers (FMM), the WSP covers only 19% of the total monthly wage bill of private companies. It also excludes foreign employees and informal workers.

Clearly, the level of support should be increased and the coverage needs to be widened. Better management and utilisation of data can help the government identify priority businesses that would require support such as businesses that have had a large share of employees test positive for Covid-19, businesses that have just started operations in 2020 and 2021, and businesses in the worst hit sectors, such as F&B, retail and tourism.

In light of the increasing need for manpower in high demand sectors such as healthcare and education, temporary jobs may also be created for job seekers who are transitioning from severely hit sectors provided they undergo the required occupational training. For example, flight attendants may be retrained as contact tracers to beef up the end-to-end process for detection and mitigation of Covid-19 transmissions. This would be a manageable transition since the role does not require any medical training. Another example includes tour van or bus drivers who can be retrained and redeployed to transport patients to quarantine centres.

In the longer horizon, there is an urgent need to reform the job market to create more sustainable, long-term and respectably-paid jobs. This can be done by increasing investment in the public health and education sectors, both considered as strategic and essential sectors for the nation if it were to build up preparedness against any future crises of pandemics as well as emerging green sectors such as sustainable agriculture, energy, transport, and waste management.

Ensuring no one is left behind

The need for a stronger social safety net in Malaysia has been emphasised well before the Covid-19 pandemic occurred. Despite efforts over the years, these social protection programmes remain fragmented causing some individuals to fall through the cracks into vulnerability.

During lockdowns, the one-off cash payments provided by the government were helpful but stopped short of serving the purpose of a social safety net. The take up for the Employment Insurance Scheme (EIS) is also only half of eligible registered employees due to its relatively recent introduction in 2018. While both the social insurance scheme provided by SOCSO (Social Security Organisation) and retirement funds by EPF (Employees Provident Fund) allow informal or gig workers to contribute voluntarily, a more thorough social protection plan is needed for informal workers not to be left out of the radar. It is reported that almost a quarter (22%) of 400 e-hailing and delivery drivers surveyed do not have any form of social safety net either in the form of life and health insurance, emergency savings, insurance against social setbacks or retirement savings.

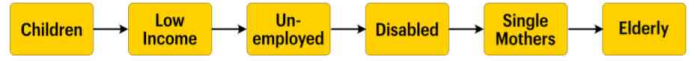

Confronted with the dynamic challenges that threaten our economic security at different stages of our lives, it is recommended that Malaysia organise its social protection ecosystem into a lifecycle approach as presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Proposed lifecycle for social protection system

Source: REFSA (2020b)

Providing universal child care benefits or subsidies to parents will not only ensure no child is left behind during this important stage of cognitive, physical and social development but also enable both parents the opportunity to earn a living and support their families. Introducing monthly cash aids amounting to the minimum wage level as support payments for affected households during pandemics or other disasters can establish a semblance of certainty and security for vulnerable groups. Ultimately, investing in comprehensive social protection infrastructure makes economic sense as it allows even the most vulnerable within the society to live with dignity and be able to contribute to the economy.

Although the pandemic has worsened social and economic divisions, behind every great crisis certainly lies a great opportunity. Undoubtedly, change requires massive political will and an even bigger societal effort. As Malaysia charts its first medium-term roadmap, the 12th Malaysia Plan, following the devastating onslaught of Covid-19, there is no better time to build back better.

References

BERNAMA (2021, Sept 28). 10,317 individuals declared bankrupt during MCO period – PM. https://www.astroawani.com/berita-malaysia/10317-individuals-declared-bankrupt-during-mco-period-pm-322336

Department of Statistics Malaysia (2021). Labour Force Survey Report, 2020. Department of Statistics Malaysia.

Niles, S. (2020. Apr 22). Wage subsidy programme, employee retention programme: What’s the difference, who can apply? Malay Mail. https://www.malaymail.com/news/what-you-think/2020/04/22/wage-subsidy-programme-employee-retention-programme-whats-the-difference-wh/1859183

Paulus, F. (2020). Revisiting the role of government in the economy. The Edge Markets. https://www.theedgemarkets.com/article/my-say-revisiting-role-government-economy

REFSA (2020a). Creating Jobs Through Public Education and Healthcare Investment. https://refsa.org/creating-jobs-through-public-education-and-healthcare-investment/

REFSA (2020b). Budget 2021:Ushering in the New Economic Paradigm https://refsa.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/REFSA_Budget2021_Oct-2020.pdf

REFSA (2021a). Strategy 2: Open Up Sectors Responsibly. https://refsa.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/REFSA_ProjekMuhibah-Strategy-2.pdf

REFSA (2021b). Strategy 1: FTTIS+V. https://refsa.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/REFSA_ProjekMuhibah-Strategy-1.pdf

REFSA (2021c). Strategy 3: Continued and Targeted Economic Assistance to Employers and Employees. https://refsa.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/REFSA_ProjekMuhibah-Strategy-3.pdf

Siti Aiysyah, T. (2020, Nov 23). Covid-19 and Work in Malaysia: How Common is Working from Home? LSE Southeast Asia Blog. https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/seac/2020/11/23/covid-19-and-work-in-malaysia-how-common-is-working-from-home/

The Centre (2020). Ensuring Social Protection Coverage for Malaysia’s Gig Workers https://www.centre.my/post/voluntary-versus-automatic-figuring-out-the-right-approach-on-social-protection-for-informal-workers

UNICEF (2020). Families on the Edge. https://www.unicef.org/malaysia/reports/families-edge-issue-1

Yunus, A. and Teh Athira, Y. (2021, Sept 21). Over half a million M40 households are now B40, says PM. New Straits Times. https://www.nst.com.my/news/nation/2021/09/729370/over-half-million-m40-households-are-now-b40-says-pm

-Published in PRAKSIS- The Journal of Asian Social Democracy on 17 November 2021.

A Tale of Two Malaysias : The Covid-19 Great Divergence

VIEW PDF HERE

By Raja Ahmad Iskandar Fareez and Morgan Loh

They called Covid-19 the great equaliser. The great leveler. Yet, it turns out that not everyone faces the same or equal hardship during the pandemic. Some, as the Orwelian saying goes, were more equal than others.

As Malaysia went into its first ever nationwide lockdown on 18 March 2020, two distinct lockdown realities emerged. One for the privileged – as many tried to cope with living in the new normal being cooped up in their own homes, they turned to popular ‘lockdown trends’ that were a craze at the time such as whipping up their own frothy Dalgona coffee, bingeing on the latest shows or their usual favourites on widely available streaming platforms, trying their hand at breadmaking, gardening, exercising, or reading, and the list goes on.

Concurrently, the less privileged had to endure a much harsher reality. Survival was and still is a daily struggle. They are often left in the lurch wondering when their next meal would be, and if they could manage to survive through the night. At times, they are at a loss as the government urges them to stay at home, yet they have no such place they can call home.

This disparity is not new. We have to recognise that the pandemic itself did not cause this inequality. But, it did widen the gap between the haves and have nots and further exposed the cracks in our system. This was further exacerbated by the then government’s response of implementing strict lockdown measures, hoping to rein in the Covid-19 outbreak. At the onset of the lockdown, the unemployment rate amongst heads of low-income households, was at roughly 25%, which was five times the national average (5.3%). For female heads of low-income households, the rate was higher at 32%. Indeed, Covid-19 was not a leveler.

Political survival trumping people’s well-being

While the health crisis continued to persist, the political turmoil in Malaysia has added insult to injury as social problems worsened. The then newly formed Perikatan Nasional administration which ascended to power via a political coup at the end of February 2020 only commanded a wafer-thin majority. It came as no surprise then that in its fixation to survive politically, it somehow neglected pursuing proactive data-backed measures to systematically address the surging cases of Covid-19. Instead, it fully relied on a disruptive strategy of perpetual lockdowns that crushed more lives and livelihoods than it did the virus.

Facing threats from its own fold, the then Prime Minister Muhyiddin Yassin resorted to calling for a national emergency which effectively suspended parliament for 7 months from January to July 2021 in hopes to stave off any attempts to remove him from office. Consequently, policymakers were denied the chance to formulate much needed policy responses to effectively address the wide-ranging impacts of the pandemic as well as keeping the government in check.

The lack of meaningful policy interventions led to worsening conditions. Since the pandemic began, more than half a million of Malaysian middle-income (M40) households earning income of between RM4,850 and RM10,959 have slipped into the bottom 40 percent (B40) income category. Meanwhile the absolute poverty figure shot up to 8.4% in 2020 from 5.6% in 2019 (pre-pandemic). Additionally, more than 10,000 individuals have been declared bankrupt during the lockdown period of March to July 2020 according to the Malaysian Department of Insolvency (MdI).

Taking matters into their own hands, kind-hearted and enterprising Malaysians banded together and initiated a crowdsourced aid distribution network dubbed the #KitaJagaKita (we take care of each other) Initiative in 2020 to match organisations with individuals who are in dire need of assistance and a separate #BenderaPutih (white flag) initiative in 2021 invoking the same community spirit to help lower income families signal distress and receive aid.

While these inspiring movements symbolise a sense of solidarity among the people, charitable acts alone are not sufficient nor are they sustainable to address the economic hardships faced by these vulnerable groups. More is needed to be done to ensure Malaysians do not fall through the cracks.

Given the systemic nature of these challenges, the state must play a role in addressing them. Amplified by the Covid-19 pandemic, Malaysians today experience the combined challenges of economic insecurity due to the destruction of jobs and the lack of social protection stemming from a fragmented system. If left unchecked, the chasm between these two Malaysian realities will only grow bigger. Thus, economic solidarity should be at the forefront of any government’s post-pandemic recovery agenda, paving the way for the nation to build back better.

The following sections delve deeper into these challenges and attempt to respond to them through a social democratic framework.

Saving jobs and livelihoods

Beyond being a means of survival, employment or jobs form an integral part of our modern identity. It gives us a sense of security, purpose and direction. Losing one’s job is akin to losing a part of oneself. As the pandemic stretched from weeks to months, safeguarding jobs must be the first line of defence in protecting Malaysians’ lives and livelihoods.

During the implementation of the nationwide lockdowns, both unemployment and underemployment rates reached record levels while approximately 768,700 Malaysians dropped out from the labour force. The reduction in work hours could signify that the lockdown has forced some full-time workers into part-time work, perhaps bringing home lower pay as well.

Graph 1 : Unemployment and Underemployment

Source: Department of Statistics Malaysia (2021). Unemployment is defined as individuals available for work and actively seeking employment. Underemployment rate refers to the rate of employed people working less than 30 hours.

Graph 2: Skilled-Related Underemployment

Source: Department of Statistics Malaysia (2021)

Within the same time-frame, skill-related underemployment also increased by 18.9% indicating a job mismatch where individuals ended up accepting jobs with lower requirements than their educational attainment. While this was steadily increasing prior to the Covid-19 pandemic, the more significant rise in 2020 may be attributed to individuals who were forced to transition into the informal sector as they faced redundancies from their previous roles. This would be applicable to pilots, flight attendants, tourism, hospitality, and other workers in sectors severely affected by the pandemic and lockdowns who then decided to take up gig work as e-hailing or delivery riders or other segments of informal work.

The grim reality is that not everyone has the luxury to work from home. In fact, only 44% of Malaysian workers were working from home at the start of Malaysia’s nationwide lockdown. Meanwhile, only one in four self-employed individuals were able to choose to work from home. In contrast, daily wage workers in the services sector have no such option and short of any modified guidelines or arrangement allowing them to work safely during a pandemic, they had to abide by the ‘stay-at-home’ order without receiving any source of income.

At a time when the private sector is struggling to maintain their businesses due to severe disruptions, the government plays a vital intervening role to minimise job losses. To this extent, the Malaysian government introduced the Wage Subsidy Programme (WSP) via its various stimulus measures to eligible employers to retain their employees. Unfortunately, according to the Federation of Malaysian Manufacturers (FMM), the WSP covers only 19% of the total monthly wage bill of private companies. It also excludes foreign employees and informal workers.

Clearly, the level of support should be increased and the coverage needs to be widened. Better management and utilisation of data can help the government identify priority businesses that would require support such as businesses that have had a large share of employees test positive for Covid-19, businesses that have just started operations in 2020 and 2021, and businesses in the worst hit sectors, such as F&B, retail and tourism.

In light of the increasing need for manpower in high demand sectors such as healthcare and education, temporary jobs may also be created for job seekers who are transitioning from severely hit sectors provided they undergo the required occupational training. For example, flight attendants may be retrained as contact tracers to beef up the end-to-end process for detection and mitigation of Covid-19 transmissions. This would be a manageable transition since the role does not require any medical training. Another example includes tour van or bus drivers who can be retrained and redeployed to transport patients to quarantine centres.

In the longer horizon, there is an urgent need to reform the job market to create more sustainable, long-term and respectably-paid jobs. This can be done by increasing investment in the public health and education sectors, both considered as strategic and essential sectors for the nation if it were to build up preparedness against any future crises of pandemics as well as emerging green sectors such as sustainable agriculture, energy, transport, and waste management.

Ensuring no one is left behind

The need for a stronger social safety net in Malaysia has been emphasised well before the Covid-19 pandemic occurred. Despite efforts over the years, these social protection programmes remain fragmented causing some individuals to fall through the cracks into vulnerability.

During lockdowns, the one-off cash payments provided by the government were helpful but stopped short of serving the purpose of a social safety net. The take up for the Employment Insurance Scheme (EIS) is also only half of eligible registered employees due to its relatively recent introduction in 2018. While both the social insurance scheme provided by SOCSO (Social Security Organisation) and retirement funds by EPF (Employees Provident Fund) allow informal or gig workers to contribute voluntarily, a more thorough social protection plan is needed for informal workers not to be left out of the radar. It is reported that almost a quarter (22%) of 400 e-hailing and delivery drivers surveyed do not have any form of social safety net either in the form of life and health insurance, emergency savings, insurance against social setbacks or retirement savings.

Confronted with the dynamic challenges that threaten our economic security at different stages of our lives, it is recommended that Malaysia organise its social protection ecosystem into a lifecycle approach as presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Proposed lifecycle for social protection system

Source: REFSA (2020b)

Providing universal child care benefits or subsidies to parents will not only ensure no child is left behind during this important stage of cognitive, physical and social development but also enable both parents the opportunity to earn a living and support their families. Introducing monthly cash aids amounting to the minimum wage level as support payments for affected households during pandemics or other disasters can establish a semblance of certainty and security for vulnerable groups. Ultimately, investing in comprehensive social protection infrastructure makes economic sense as it allows even the most vulnerable within the society to live with dignity and be able to contribute to the economy.

Although the pandemic has worsened social and economic divisions, behind every great crisis certainly lies a great opportunity. Undoubtedly, change requires massive political will and an even bigger societal effort. As Malaysia charts its first medium-term roadmap, the 12th Malaysia Plan, following the devastating onslaught of Covid-19, there is no better time to build back better.

References

BERNAMA (2021, Sept 28). 10,317 individuals declared bankrupt during MCO period – PM. https://www.astroawani.com/berita-malaysia/10317-individuals-declared-bankrupt-during-mco-period-pm-322336

Department of Statistics Malaysia (2021). Labour Force Survey Report, 2020. Department of Statistics Malaysia.

Niles, S. (2020. Apr 22). Wage subsidy programme, employee retention programme: What’s the difference, who can apply? Malay Mail. https://www.malaymail.com/news/what-you-think/2020/04/22/wage-subsidy-programme-employee-retention-programme-whats-the-difference-wh/1859183

Paulus, F. (2020). Revisiting the role of government in the economy. The Edge Markets. https://www.theedgemarkets.com/article/my-say-revisiting-role-government-economy

REFSA (2020a). Creating Jobs Through Public Education and Healthcare Investment. https://refsa.org/creating-jobs-through-public-education-and-healthcare-investment/

REFSA (2020b). Budget 2021:Ushering in the New Economic Paradigm https://refsa.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/REFSA_Budget2021_Oct-2020.pdf

REFSA (2021a). Strategy 2: Open Up Sectors Responsibly. https://refsa.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/REFSA_ProjekMuhibah-Strategy-2.pdf

REFSA (2021b). Strategy 1: FTTIS+V. https://refsa.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/REFSA_ProjekMuhibah-Strategy-1.pdf

REFSA (2021c). Strategy 3: Continued and Targeted Economic Assistance to Employers and Employees. https://refsa.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/REFSA_ProjekMuhibah-Strategy-3.pdf

Siti Aiysyah, T. (2020, Nov 23). Covid-19 and Work in Malaysia: How Common is Working from Home? LSE Southeast Asia Blog. https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/seac/2020/11/23/covid-19-and-work-in-malaysia-how-common-is-working-from-home/

The Centre (2020). Ensuring Social Protection Coverage for Malaysia’s Gig Workers https://www.centre.my/post/voluntary-versus-automatic-figuring-out-the-right-approach-on-social-protection-for-informal-workers

UNICEF (2020). Families on the Edge. https://www.unicef.org/malaysia/reports/families-edge-issue-1

Yunus, A. and Teh Athira, Y. (2021, Sept 21). Over half a million M40 households are now B40, says PM. New Straits Times. https://www.nst.com.my/news/nation/2021/09/729370/over-half-million-m40-households-are-now-b40-says-pm

-Published in PRAKSIS- The Journal of Asian Social Democracy on 17 November 2021.

RESEARCH

PILLARS

RESEARCH

CATEGORIES