Nazir is the founder of Tintabudi, an independent bookshop in Kuala Luumpur specialising in literature, philosophy, history, and arts.

There are no signboards to be seen. You would have to take a flight of narrow stairs to the first floor of The Zhongshan Building – an artist collective nested in a newly restored 1950’s building at the periphery of Petaling Street, Kuala Lumpur– before coming across Tintabudi.

Tintabudi bookshop is small but vibrant. On a good day, which is one not hampered by the COVID-19 pandemic, you’d hear the constant tinkering of a bell as the door to Tintabudi opens and closes to new patrons. Inside, they shuffle shoulder to shoulder along narrow walkways to browse the latest books and magazines. Behind the bookshop is a cafe, equally small, but always crowded. Echoing throughout the building, one would hear the laughter and murmuring of cafe aficionados whiling time away in this little corner.

Today, both the bookshop and the cafe are closed as the whole of Kuala Lumpur and the Klang Valley falls into the lockdown slumber. Everything comes to a standstill and together, businesses wait patiently and anxiously to resume their activities like they used to.

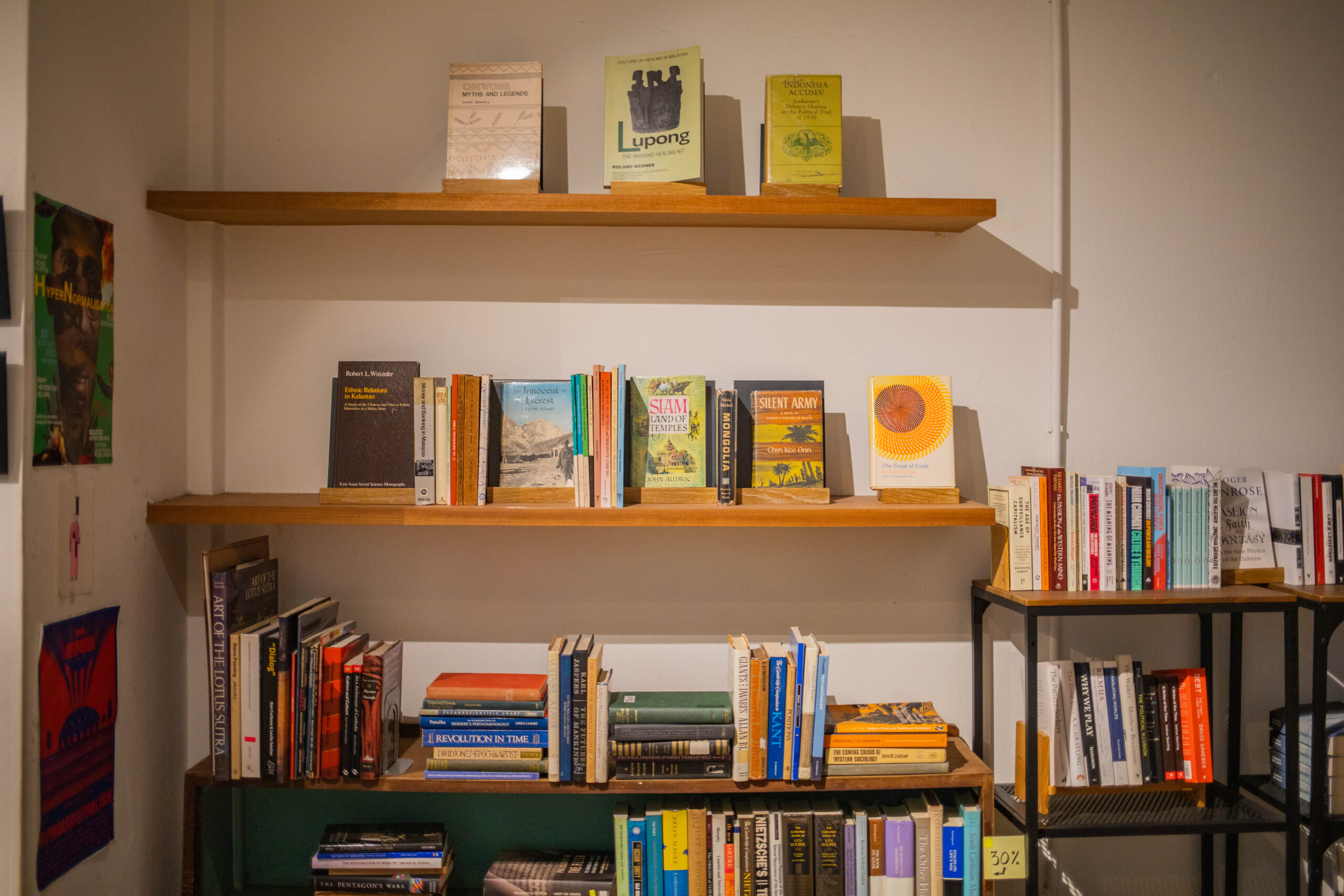

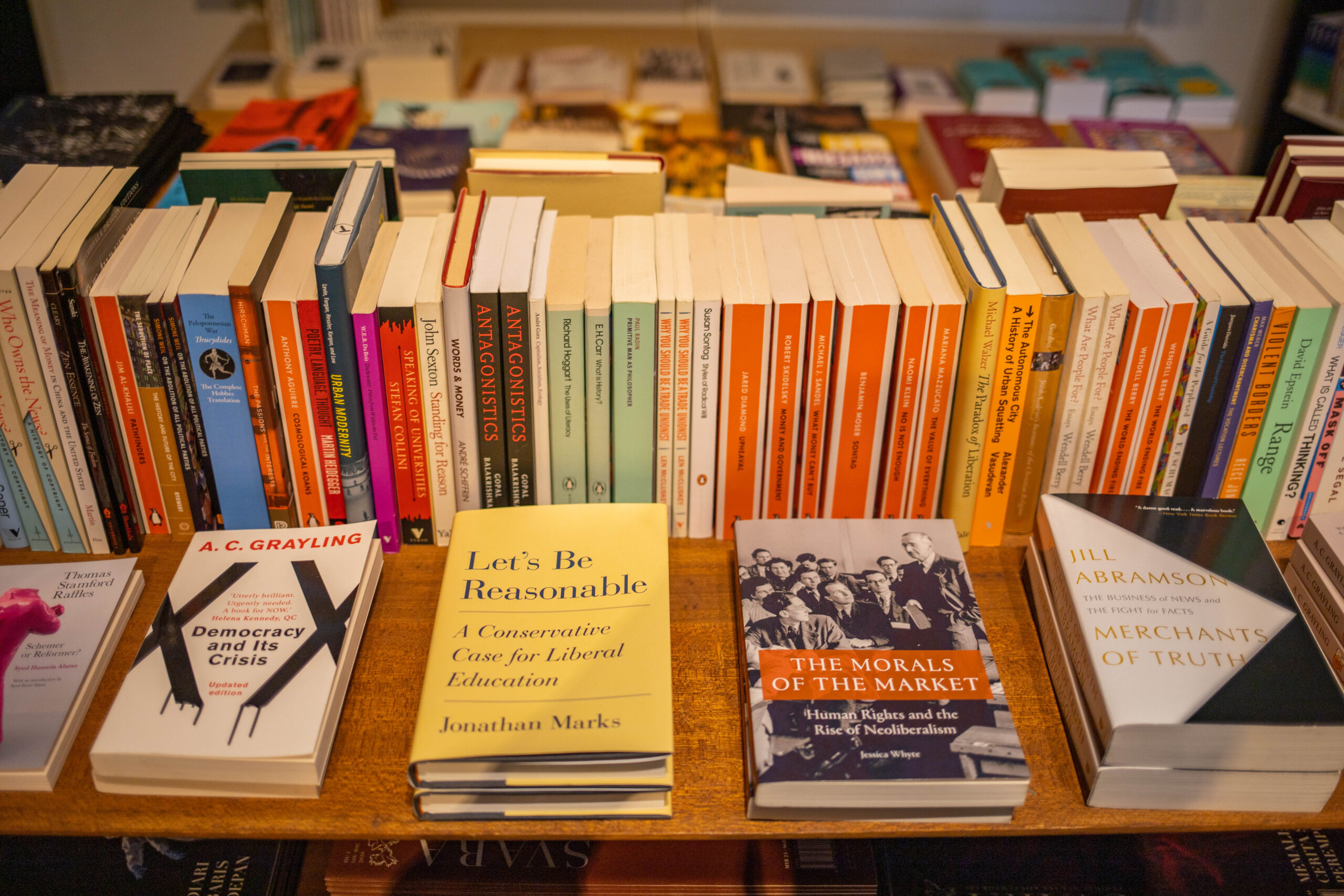

Tintabudi’s carefully curated collection of new and used books

Tintabudi’s carefully curated collection of new and used books

As Tintabudi closes its physical shop, Nazir realises the challenges he will have to face to sustain his income. To keep his business running, he had set up an online store and arduously pushed sales on Instagram, where most of his customer base now reside.

“ […] Online works for [larger] volumes. But for us, we are not that big,” said Nazir, alluding to the challenges of logistics and distribution. However, he was quick to add that he was one of the lucky ones, being able to cater to a niche community of readers that are both internet-savvy and affluent. Other people and creators in the arts industry, however, may not enjoy the same benefits. Performing artists or visual artists, for example, would have to find other methods to reach a paying audience. As a result, they often have to resort to alternative ways of earning an income, either through side gigs or full-time jobs, effectively putting their creative pursuits to a halt.

“The problem with Malaysia is that our [creative] market is not big. When the market is small and you have this kind of pandemic, it can easily affect your revenue stream because you cater to a much smaller demographic of people,” Nazir explained.

Waiting for the next customer.

Waiting for the next customer.

While the government provides grants to artists and arts-based organisations in Malaysia, these are usually handed out to already-prolific and successful organisations. This process is counter-productive to supporting smaller and less well known arts groups.

“What’s weird about Malaysia [is] you need to have a name outside, then the government will come to you and offer you grants”, Nazir pointed out.

What he hopes for instead, is a more proactive approach to address the needs and livelihoods of artists and the creative spaces they thrive in.

“A bookshop is not just a bookshop. It’s a location for people to discuss ideas…[it’s an] ecosystem.”

When asked about how independent businesses like Nazir’s would benefit from government support, Nazir stresses the importance of creating a support network with a reliable government body at the crux of it.

“[It’s not just about] giving out money, which is helpful, but building a robust, sustainable ecosystem,” said Nazir.

He’s right. Spaces like Tintabudi and The Zhongshan Building are not just marketplaces. They are spaces for diverse communities to convene, commune, and collaborate. As many have seen with the proliferation of creative hubs over the last few years – Tun Perak Co-op, The Godown, and REX KL, to name a few – the arts industry is increasingly important to the economic, social, and cultural well being of urban spaces. It shapes the ebb and flow of a dynamic urban community and brings life to otherwise deserted city spaces.

During the lockdown, spaces like Tintabudi had to rely on the goodwill of their landlords to provide rental subsidies and support. Nazir shares his thoughts with REFSA.

During the lockdown, spaces like Tintabudi had to rely on the goodwill of their landlords to provide rental subsidies and support. Nazir shares his thoughts with REFSA.

In your opinion, what can the Malaysian government do to create an ecosystem that supports the distribution, selling, funding, and demand of creative outputs? Share your thoughts with us in any of our social media channels and tag your favourite arts and cultural spaces.

Follow and support Tintabudi on Instagram at @tintabudi.