PRESS

ROOM

OCT 24, 2016

Post Duterte’s visit, is China a real bully?

COMMENT Those who expected the Manila government to win its bid for the disputed Spratly Islands at Hague could not have possibly foreseen the landslide victory that the Arbitration Court delivered to Manila.

The verdict, delivered by the Permanent Court of Arbitration in Hague on July 12, has nullified China’s historic rights within the ‘Nine dash line’, and it decided that all of Spratly’s features are nothing but groups of rocks, and condemned China’s reclamation as having violated the United Nations Convention of Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) and the rights of the Phillipines in the disputed exclusive economic zone. In short, the Philippines won almost all of its submissions.

While the Manila government was still overwhelmed by the verdict of arbitration, the reactions of China are closely monitored by all concerned claimants and interested parties. Beijing has often stated that the ruling is “nothing but a piece of useless paper” to China.

After few months, however, the ruling has not changed the situation nor softened the confrontation between Philippines and China. As a result, one should think a new way to get out from this stalemate, and the president of Philippines Rodrigo Duterte did it.

The ruling is valid and legitimate

The ruling which was made in accordance to the provisions of UNCLOS is a valid and legitimate verdict. As stipulated under Article 286 of UNCLOS which reads “…any dispute concerning the interpretation or application of this Convention shall, where no settlement has been reached by recourse to section 1, be submitted at the request of any party to the dispute to the court or tribunal having jurisdiction under this section”, it permits a state to submit a dispute unilaterally for compulsory procedures entailing binding decisions.

Article 287 further allows the state to choose the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea, or the International Court of Justice, or an arbitral tribunal constituted in accordance with Annex VII of UNCLOS, or a special arbitral tribunal constituted in accordance with Annex VIII of UNCLOS, for the settlement of disputes concerning the interpretation or application of this Convention.

The3 Philippines had chosen to refer the case to the Permanent Court of Arbitration by invoking Annex VII of UNCLOS. The absence of China before the tribunal would have not nullified the legitimacy and legality of tribunal’s proceedings and verdict as stipulated under the Article 9 of Annex VII which reads “If one of the parties to the dispute does not appear before the arbitral tribunal or fails to defend its case, the other party may request the tribunal to continue the proceedings and to make its award. Absence of a party or failure of a party to defend its case shall not constitute a bar to the proceedings…”.

Article 10 of Annex VII further reads “The award shall be final and without appeal, unless the parties to the dispute have agreed in advance to an appellate procedure. It shall be complied with by the parties to the dispute.”

When China ratified the UNCLOS in 1996, it must have known that it could not acknowledge or reject parts of the UNCLOS selectively. So, even if China were humiliated and hurt by this settlement, the ruling is still legally-binding and valid. Moreover, the ruling is landmark ruling that has become part of international law, where it can and will be cited in any future similar cases.

Mixed responses toward the ruling

In terms of responses from the international community, there were seven countries which have “publicly called for it (the ruling) to be respected, 33 countries that have issued generally positive statements noting the verdict but have stopped short of calling for the parties to abide by it, nine countries that have made overly vague or neutral statements about the South China Sea without addressing the ruling, and five which have publicly rejected it,” according to the Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative.

Regionally, Vietnam and Philippines were expectedly urging compliance with the ruling, Myanmar and Malaysia took note of it, and Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Thailand and Laos issued neutral statements without mentioning the ruling.

Nevertheless, the UNCLOS stays silence on how to implement the ruling, particularly when the other party has stated explicitly it would not acknowledge the verdict of unilateral initiated compulsory settlement. Furthermore, neither United Nations nor the tribunal can implement the ruling, especially when the other party is one of permanent members of UN’s Security Council.

The implementation has become a taboo though the ruling is already part of instruments of international laws.

Excluding the Philippines, the aforementioned countries urging that the ruling be respected are the United States, Australia, Japan, Canada, New Zealand and Vietnam. Then, the Philippines looks for assistance from the United States, Japan and Australia, and they did act verbally, but not physically.

On the Asean side, its Foreign Minister met for the first time in Vientiane, Laos, after the ruling on July 24, then the 19th Asean-China Summit and the key Asean Summit took place on Sept 7, three of them issued joint statements without mentioning the Hague ruling. Indeed, this is a big setback for Philippines.

In the following few months after the ruling, China has continued flying its flag over the disputed areas and continuously beefing up its military exercises at the South China Sea. The climax of it was the conduct of joint naval exercise between China and Russia in South China Sea in September this year.

The message China tries to send out is that it is ready to use necessary force to thwart any attempt of carrying out the ruling in the name of protecting its integrity of territory. Apart from that, Vietnam was reportedly deploying long range rocket launchers to disputed features, which added more fuel to the already fiery situation.

Defusing the tension

The original purpose of Manila in seeking arbitration was to achieve peaceful settlement without resorting to the use of force. If the ruling resulted in serious armed conflicts among the claimants, it would defeat the original purpose of arbitration. Although it sounds cruel, the Philippines does not have any more options to manoeuvre China in this game of power.

Depending on its ally, the United States, to implement the ruling is simply unrealistic because United States itself is in mixed situations with China. On one hand, China’s support is needed in handling various international crises like North Korean nuclear tests, implementation of Iran’s nuclear deal and reconciliations in Afghanistan; on the other hand, China is a major trade partner and debtor with United States.

Put simply, the United States will not confront China directly and openly, but it is encouraging Philippines to confront with China face to face. Eventually, Philippines and China might end up in unavoidable scenario of bloodshed but the United States remains intact. Philippines should avoid the trap if it values its national interests.

In fact, resorting to international arbitral tribunal is always the last resort for desperate states because the ruling is final and non-appealable according to the UNCLOS, unless otherwise agreed upon by related disputants. Since the 712’s ruling was a unilateral arbitration and no bilateral agreement was reached, Philippines has reached its dead-end in terms of legal means.

By law, the ruling will be part of international law until there is another instrument which supersedes the validity of it. Although it is highly unlikely to happen under the current atmosphere, China and Philippines can explore the possibility of negotiating a bilateral treaty in good faith, to set aside the ruling in a subtle way without jeopardising the latter’s interests.

The instrument is meant to defuse the tense and gridlocked situation and should lead both nations to resume the peaceful settlement of a bilateral dispute.

But the most difficult part is how to convince United States and its allies to accept that China will not bully Philippines in any bilateral talks and to stay neutral. In the eyes of western world, China is painted as an aggressor and big bully in handling overlapping border issues, but history tells us otherwise.

Is China a bully?

Historically, China always get highlighted over its history of engaging into wars with Soviet Union, India and Vietnam because of border issues, which implies China is a bully. But the latter three countries clashed even much more seriously with their neighbouring countries in the past. For examples, Soviet Union invaded Finland in 1939, India clashed with Pakistan over Jammu and Kashmir area, and Vietnam was well known for its invasion of Cambodia.

China is not an angel, neither India nor Vietnam, too.

China, however, is not so aggressive if we look at its track record.

Firstly, before 1953, China laid its ‘Eleven Dash Line’ claim which covered almost the entire South China Sea. In the name of preserving “comradeship and brotherhood” with North Vietnam, China removed two dash lines which were near to Gulf of Tonkin resulted in the creation of today’s ‘Nine Dash Line’. China compromised.

Secondly, in a secretive bilateral border treaty with North Korea, China ceded a ‘100-square-mile area involving Mount Paektu/Changbai Shan’ to North Korea during the visit of President of China, Liu Shao Qi, to Pyongyang in September 1963. China compromised again.

Thirdly, after long discussions and armed conflicts, China and Russia reached a peaceful agreement to settle their eastern overlapping claims. They agreed to split the Heixiazi Island or Bolshoi Ussuriysky Island into half and occupied by each side in 2004. By right China should insist taking back the entire island which was part of the Qing dynasty a century ago, but China compromised.

Fourthly, when Tajikistan’s Lower House ratified 2002’s Sino-Tajikistan border agreement in January 2011, Tajik Foreign Minister, Khamrokhon Zarifi said “hailed the border deal as a ‘great victory’ for Tajik diplomacy, noting that China had previously claimed about 20 percent of the country’s territory.”

Looking at the old historical record, the area China had dropped its claim was part of territory administered by Qing dynasty. Being the successor of the Qing dynasty, communist China did not persist in the matter but decided to compromise.

These four cases show China was willing to embark on peaceful border talks, willing to drop ancient claims based on history, and willing to cede “sacred and inviolable” (Chinese favourite terms) territory to other parties for the sake of maintaining peaceful bilateral relations and achieving mutual acceptable border agreements.

That is why bilateral talks are favoured by China because compromises can only be made on a mutual basis, and without interference from a third party.

Preserving its dignity is a great concern for China. To be sure, western analysts purposely won’t tell us these facts, so we have to do our homework to find out how China really behaved in the past.

Options for Malaysia

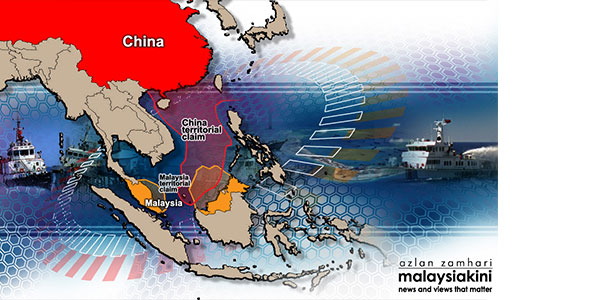

On the Malaysian side, we have stated in a Communication to the Hague’s tribunal that “Malaysia is not bound by the outcome of the arbitral proceedings or any pronouncement on fact or law to be rendered by the Arbitral Tribunal.”

And in its post ruling statement, Putrajaya took note of the Award without calling for compliance for any party, but emphasising full adherence of all parties to the Declaration and UNCLOS.

Although the Philippines may have lost confidence towards Asean, there is no better multilateral platform than that to manage the conducts of parties in South China Sea. In fact, Asean is still the best proven platform to deter the claimants from militarising the situation. Perhaps there are a lot of critics against the effectiveness of Declaration of Code of Conducts in the South China Sea, but this multilateral instrument provides for almost a decade of regional stability and peace.

A major point that tends to be overlooked by many sides is, China refuses to embark on any multilateral instrument negotiation, except for the Declaration.

The Declaration is not a legal binding instrument, but the Treaty of Amity and Cooperation (TAC) is. China became a contracting party in October 2003. Phrase (d) of Article 2 of the TAC requires the High Contracting Parties to embark on settlement of differences or disputes by peaceful means, and phrase (e) requires signatories to renounce the threat or use of force.

Any violation of it will prompt the contracting parties to file a case before United Nations or International Court of Justice to seek international concerted sanctions against any aggressor.

Recalling the aforementioned that China wasn’t a bully by its track record, it is advisable to engage China for the conducts of in the South China Sea under current multilateral arrangements like the TAC and Declaration. With regards to the overlapping sovereign claims, there is no harm to start bilateral negotiation with China.

Who knows China may agree to remove two more dash line which lie above Sarawak and Sabah’s waters and redraw the line which accepted by both parties in a bilateral talk between Malaysia and China, for example.

In essence, the South China Sea dispute is about overlapping sovereign claims, not the struggle for hegemony between China and United States. For perpetual peace wise, the claimants should utilise the incumbent multilateral instruments to resolve the disputes. And, it is better to keep the dispute within the scope of overlapping sovereign claims instead of letting the realist kind of power struggle taking charge.