IN THE

NEWS

APR 19, 2020

Beefing up food security

By Dina Murad, The Star

The Covid-19 pandemic has put the spotlight on Malaysia’s immediate and long term plan for food security.

EMPTY shelves. Long queues. People squabbling over bread.

Pictures of people hoarding massive amounts of food which circulated widely on the Internet in the early days of the movement control order (MCO) sent a ripple of fear among many about Malaysia’ food supply. After all, who would have thought before the Covid-19 pandemic that bread would become such a hot commodity and be snapped up as soon as shelves were restocked. Then came the photos of farmers disposing of tons of fresh produce as they encountered problems moving food from farms to the table.

While panic buying has significantly subsided, and logistics issues for fresh produce are quickly being resolved, these images have sparked some concern about how self-sufficient the country is in food to endure future emergencies and possible trade disruptions.

It cannot be denied that the coronavirus has underscored the importance of food security – the guaranteed access to a sufficient quantity of affordable, safe and nutritious food.

According to agricultural and resource economics specialist Prof Datuk Dr Nasir Shamsudin, despite the pandemic, Malaysia’s food supply has mostly been stable.

As of now, the full impact of the pandemic on food security is not yet known, says Prof Nasir who is a professor in Agricultural Economics at Universiti Putra Malaysia (UPM).

“Disruptions in the food chain are minimal as the food supply has been adequate and markets have been stable so far except for isolated cases in the Cameron Highlands.

“In general food availability is not a problem. The problem will be – and there already has been some minimal impact from this – with the movement of the food from the farm to consumers, ” he says.

To counter the repercussions of the MCO, on March 31, Prime Minister Tan Sri Muhyiddin Yassin announced an allocation of RM1bil towards food security to ensure sufficient food supply over the critical period. The MCO started on March 18 and is expected to be lifted after April 28.

Yesterday, Agriculture and Food Industries Minister Datuk Seri Dr Ronald Kiandee told Sunday Star that a Cabinet Committee on Food Security chaired by the Prime Minister will be established soon to formulate the National Food Security Policy.

“What is important now is that the authorities should continue to closely monitor food prices, ” Prof Nasir says.

The government should also ensure the effective delivery of agricultural inputs including feed, and ensure the smooth logistical operations of regional food supply chains. Malaysia must also have adequate stockholding in the form of strategic food security reserves as a first line of defence in emergencies. In light of the current situation, it is important that trade continues to flow and for Malaysia to make full use of the international market as a tool to secure food supply and demand, says Prof Nasir.

Malaysia still import-dependent

With the exception of poultry, eggs, pork, and fisheries, Malaysia depends on imports of most of its food items, says Prof Nasir.

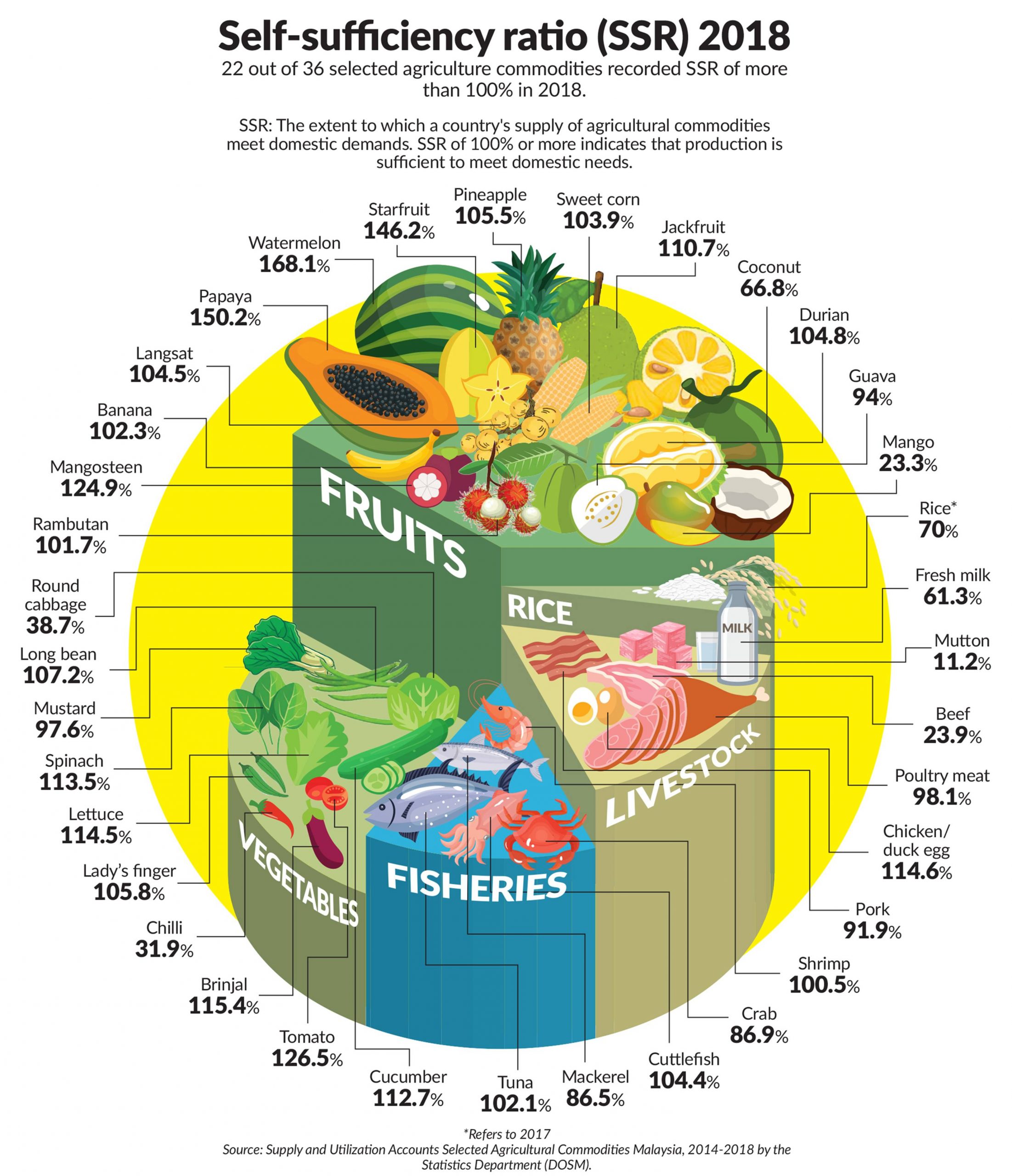

“In 2019, the country had yet to reach self-sufficiency in the main foods, with self-sufficiency in rice at 70%, vegetables at 46.6%, beef at 23.9%, mutton at 11.2%, fresh milk at 61.3%, dairy products at 5%, and fruits at 79%. This has also caused a trade deficit that has been increasing from year to year, ” he explains.

The above are aggregate numbers calculated by UPM based on data from the Statistics Department.

“In 1990, the food trade deficit was RM1.1bil. In 2006, it increased to RM8.5bil due to higher import growth, and in 2016, the trade deficit was RM18.6 bil, ” says Prof Nasir.

In 2018, Malaysia’s food import hit RM50bil. Nevertheless, Prof Nasir notes that several food security programmes that address availability, accessibility, utilisation, and stabilisation of food supplies as mentioned in the National Agrifood Policy have been implemented successfully.

Moving forward, Prof Nasir says the country should concentrate on resolving factors that have caused lagging in the food sector. This means finding solutions for under-investment in agricultural research, small-scale farms with low levels of technology, improving entrepreneurship, and addressing climate change and depleting resources.

Among the many measures to improve Malaysia’s future food security suggested by Prof Nasir are empowering the role of cooperatives in the food supply chain and improving farmers’ income.

“In order to increase the productivity of food production, the sector also needs entrepreneurs who can commercialise high-tech food production, ” he adds.

Prof Nasir believes that the present food production sector must be developed and transformed into a modern, competitive and commercially vibrant sector.

“This can be achieved by emulating the industrial crop production model to the food sector where large, private sector-led plantations co-exist with the smallholder production units, ” he says.

According to Khazanah Research Institute’s (KRI) July 2019 discussion paper “Achieving Food Security For All Malaysians”, Malaysia is more food secure today by various internationally accepted criteria, compared with the past, as all major foods are available in sufficient quantities to meet market demand. It noted, however, that demand should not be equated with human needs.

The report found that food access is no longer a problem for most Malaysians but food affordability remains an issue.

Prof Nasir predicts that in the coming decades, the food sector in the country will face major challenges. These include providing sufficient food to meet a growing population and rising per capita income as well as dietary changes, eradicating hunger and adapting to the impacts of climate change.

As most of the productive land in Malaysia is now being utilised, future increases in food production will have to rely on increasing agricultural productivity, says Prof Nasir.

“To ensure the supply of quality and safe food at affordable prices, investment in food production should not only be evaluated in terms of private benefits but social returns also, such as the country’s security and peacefulness. This requires a mix between food policy, technology and entrepreneurship.

Improved food supply chain

KRI senior research associate Dr Sarena Che Omar predicts that Malaysia may come out of the pandemic with improved effectiveness in its local food supply chain.

“The good news coming out of this crisis is that Malaysia was forced to focus on the effectiveness of our local food supply chain, and to learn to appreciate its importance.

“Prior to the MCO, we took the supply chain for granted, and whenever we think about the food industry, we only think about the farming segment, ” says Sarena.

In the beginning of the MCO period, many problems were reported within the food supply chain which affected production, logistics and distribution of produce. The government, NGOs and farmers’ associations had to quickly step in to resolve the issues so that food could reach consumers in time.

The government has also implemented measures to ensure the food supply chain will not be disrupted.

“It is hoped that post MCO, we will enjoy more efficient food supply chains and that the public appreciates all the parties involved in bringing the food from the farm to the table, ” Sarena tells Sunday Star.According to the 2019 Global Food Security Index, Malaysia was ranked 28th out of 113 countries and is in the “good performance” category.

“We did far better than our neighbouring countries: Indonesia was at 63, Thailand at 52, the Philippines 64, Cambodia 90 and Vietnam 54. But we were not as high as our closest neighbour, Singapore, at 1.

“A key weakness is that Malaysia, relative to the other 112 countries, spends less public expenditure on R&D. But we fared well in terms of providing financing services to our farmers, with having a low proportion of the population below the global poverty line, and with having food safety programmes, ” she observes.

Malaysia produces about 70% of the rice it consumes. However, Sarena explains that we also currently have enough in the country to feed the population for at least half a year in the event of an emergency.

Another impact of the MCO is the loss of farm workers.

“During the MCO period, Malaysia may have lost a lot of our migrant workers who are not covered under the Prihatin economic stimulus programme, ” says Sarena, who foresees that employers across the food supply chain may be forced to innovate to reduce their dependence on having many workers.

Disruptions of the global supply chain may also cause issues with some imported items.

“Luckily in terms of food, the main food items such as rice, vegetables, chicken meat and eggs, are more than 60% produced locally. So even if we see international disruptions, it may only have an impact on luxury food items such as beef, imported fruits and premium seafood, ” she says.

The key thing is to acknowledge that there may be disruptions and life may not go back to pre-Covid norms for some time. However, it is likely to be more of an inconvenience rather than a dire situation for Malaysians, given our relatively stable state of food supply and food security, she says.

Preparing for the future

In the event that another crisis like this occurs in the future, Malaysia should already have a list of essential sectors pre-approved to move on as usual so as to minimise the period of uncertainty and adjustment, says Sarena.

“It needs to be made clear that people in this sector can continue working, and they should be given priority in terms of access to personal protective equipment (PPE) and health and safety guidelines, ” she says.

On a similar note, Malaysia should have pre-approved shelters and food distribution centres in the event of an emergency like this, says Sarena, who adds that bread should be included as an essential food item.

Prompt and continuous media engagement should also be provided by the relevant ministries and appointed task force to assure the public that there is sufficient food and prevent panic buying or hoarding.

Still, climate change will significantly impact Malaysia’s food security.

Rising temperatures, changing weather patterns, and the increasing prevalence of floods and pest populations will all hamper food production yields over the coming years, says Research for Social Advancement think tank lead researcher Darshan Joshi.

“Our yields are already quite low – rice is a perfect example here – due to a general lack of R&D and and innovation, low rates of capital formation and mechanisation, andunsustainable farming practices, ” he says.

“Climate change will worsen all of this in the absence of structural changes that address each of these areas where we are lacking and investment in more future-proof farming technologies like resilient crops and vertical farms.”

Darshan argues that a greater understanding of the impacts of climate change on crop resiliency and yields is necessary. With that in mind, grants should be extended to universities and laboratories to develop high-yield, resilient crops which will survive as temperatures rise and weather patterns become more unpredictable, he says.

“Overall, we now import around a quarter of the food we consume. When we break things down further, we see that especially for cereals (including rice), fruits, and vegetables, we are deeply in the red in terms of imports over exports. This wasn’t really the case in the 1990s, and it has been since the early 2000s that we have begun importing a lot more, ” he says.

Bank Negara Malaysia’s quarterly bulletin for the third quarter of 2019, “Food Imports and the Exchange Rate: More Than Meets the Eye”, showed that Malaysia is a net food importer, with imports forming about a quarter of total food supply. However, the report also noted that Malaysia is self-sufficient for a considerable number of food items although its total import content for food (24%) is not insignificant.

“For both fruits and vegetables, our self-sufficiency ratios were around 90% in 2000 compared with roughly 80% for fruits and under 60% for vegetables in 2015. This is despite land use for vegetable crops having doubled in that time, albeit from a very low benchmark, ” Darshan says.

More funding should be allocated towards R&D and innovation within the agricultural sector in order to raise yields and improve the livelihoods of farmers, says Darshan.

It is time to put more emphasis on vertical farming and indoor farms, a nascent industry in Malaysia, he adds.

“As food is increasingly grown closer to markets, we will be able to minimise the distribution issues we see under the MCO today. We would also be supporting an industry that, given the effects of climate change, will play a big part in the future of agriculture, ” says Darshan.

“Although vertical farming today is primarily limited to the growing of leafy vegetables, funding for research could enable breakthroughs in the development of techniques to grow fruit and grains indoors as well. All this bodes well for Malaysia’s food security, during normal times and in times of crisis.”

— THE STAR