For the last few decades, Gross Domestic Product (GDP) has enjoyed a preeminent position in policymaking and national planning. Though it began life in the 1930s as an economic indicator to estimate the total value of a country’s production, GDP has transformed into a tool with considerable political leverage these days.

Indeed, the pursuit of high GDP growth has become akin to the holy grail for politicians, serving as a key performance indicator – a benchmark of ‘success’. To add to its glamour, international organisations like the World Bank use variants of GDP, including per capita measures adjusted for population size, to compare nations’ development levels.

What is often forgotten amidst all of this glorification is that GDP is not a fact of nature like gravity. Instead, it is the product of a system of accounting using a series of estimations. And as a result, it is by no means perfect. Its appropriation into politics has perpetuated even more misconceptions about the true meaning of GDP.

This note therefore aims to answer two crucial questions: what does GDP really mean and in what ways is it flawed as a metric of development?

What GDP is

Definition and measurement

GDP is the ‘total value of production’ in a country during a given period, most commonly a year. It is measured by calculating the ‘total amount spent on final goods and services’ produced in a country as follows:

GDP = C + G + I + (X-M), where

- C is (private) consumption, which refers to final household expenditure on durable goods, nondurable goods and services. Examples include food, rent, petrol, etc.

- G is government spending (or government consumption) on final goods and services. Examples include civil servant wages, public infrastructure spending, etc.

- I is investment (or gross capital formation), which captures business investment. Examples include buying machinery for a factory, buying equipment for an office, etc.

- X is exports, which captures the value of goods and services produced domestically but sold abroad.

- M is imports, which are subtracted because the consumption of imported goods is already counted under C, G and I and because their production took place abroad.

Each country’s national statistical office compiles this data from many administrative and statistical sources, including surveys of businesses and households, tax declarations as well as censuses, in line with agreed upon international standards.

The final GDP value can be expressed in nominal or purchasing power parity (PPP) terms. Nominal GDP simply gives the value of production in current market prices converted to USD to allow for international comparisons. However, such a measurement does not account for differences in cost of living or exchange rate fluctuations over time. Meanwhile, PPP GDP takes the local prices of goods and services into account to ensure that currencies are valued appropriately.

Uses of GDP

The economy is a complex machine with many moving parts – composed of industries, consumers, government and other agents – that all interact with one another in many different ways. Decision makers need a number to make sense of all the economic transactions that take place within and between the players. That is where GDP and its variants come in.

The reason for stating “and its variants” is because on its own, GDP is not a meaningful measure. Instead, it is the metrics derived from GDP, including GDP growth and GDP per capita, that are used for policymaking and planning purposes:

|

Indicator

|

Meaning and use

|

|

GDP growth

|

Measures the increase in GDP from one period to another. Gives policymakers an idea of where a country is headed relative to its past performance.

|

|

GDP per capita

|

Measures economic output per person – obtained by dividing GDP by population. Gives policymakers an idea of standard of living compared to other countries.

|

|

Gross National Income (GNI)

|

Measures total output by residents of a country, both domestically and abroad. This includes income earned by residents working/investing abroad and excludes income earned by foreigners inside the country. The World Bank classifies countries by income level (e.g. high income, upper-middle income, etc.) based on GNI per capita.

|

GDP growth gives policymakers an idea of which economic sectors are the most productive and therefore worth prioritising as part of the national development agenda – such as high-value added manufacturing and skilled services. The indicator also informs the government and central bank’s decisions on tax and interest rate policies: if the economy is growing below par, stimulus measures may be needed.

The relationship between GDP growth and GDP per capita is also of interest, as the next sub-section illustrates.

High GDP growth and a high GDP per capita tend to be associated with increasing prosperity. From a purely arithmetic standpoint, if GDP grows faster than the population, then GDP per capita grows as well. Higher per capita output in turn is correlated with a better standard of living.

In this regard, the World Bank classifies nations by income level based on output per capita, with the threshold for high income defined as a GNI per capita of $13,205 or more. Accordingly, countries that fulfil this definition are mainly in Western Europe, North America and East Asia, regions which generally enjoy a higher life expectancy, lower absolute poverty and better educational outcomes than sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America and South Asia.

What GDP is not

-

A measure of standard of living

It is important to remember that correlation does not imply causation. In other words, even though GDP growth and poverty reduction are related as we saw above, it does not mean that more growth automatically leads to lower poverty. This is because GDP does not capture the distribution of income across an entire population, even in per capita terms.

GDP does not acknowledge that corruption, rent seeking behaviour and other leakages can prevent economic growth from benefitting the average citizen. On its own, GDP also fails to account for urban-rural or ethnic inequality on the back of differences in productivity, wages as well as policies.

As a gross measure, GDP is only concerned with output and not the means to achieve that output. GDP does not put a value on any destruction, whether environmental or otherwise, that happens along the way in pursuit of higher production.

Therefore, treating GDP (growth) as gospel can be dangerous because it may lead policymakers to understate the unmeasurable negative effects of growth, such as pollution and loss of biodiversity.

Economist Frédéric Bastiat illustrated this problem through the ‘parable of the broken window’. In essence, if a household’s window is broken and a repairperson is hired to restore the window to its initial state, the household is effectively increasing GDP. This is because the broken window is an income opportunity for the repairperson, who would in turn contribute to consumption by buying bread from the baker and so on.

But despite the gain in GDP, fixing the window is simply a maintenance cost that does not promote productivity or significant net welfare gains.

The parable highlights GDP’s inability to take opportunity cost – the hidden cost of taking one action instead of the best alternative – into account. If the window had not been broken, the money that went towards fixing the window could have been spent on more welfare-enhancing and value-adding consumption or investment. Unfortunately, GDP ignores this dimension of decision making.

To evaluate the financial health of a business, it is not enough to look at its annual profit and loss statement. The balance sheet, with its profile of assets and liabilities, is also needed to paint a better picture of what the company is worth.

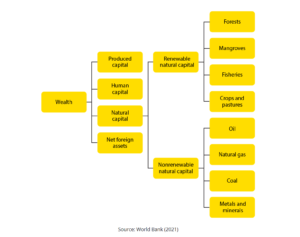

Similarly, GDP only tells us the income of a country at a point in time, not its wealth or the state’s ability to manage resources – assets – over time. As the figure below shows, the composition of wealth is much broader than just what is directly produced. National income and wealth may therefore not always rise or fall concurrently.

GDP may grow in the short-run because of the exploitation of a nonrenewable resource like oil, but if the country fails to diversify its sources of income, the eventual depletion of the resource will reduce its stock of wealth.

Indeed, the World Bank found that 26 countries recorded negative wealth per capita growth between 1995 and 2018, mostly in sub-Saharan Africa. A continuation of this trend implies that future generations will be worse off in these countries, whether due to dependence on depleting commodities with fluctuating prices or lack of investment into a wealth-generating asset like human capital (through education and healthcare) or renewable natural capital.

Once again, narrowly pursuing a quick boost to GDP growth does not do a country any favours. As we have seen, GDP growth today can make a nation poorer in the future if there is no effort to promote sustainable development through the careful management of assets like human, natural and produced capital.

Conclusion

GDP has its place in policymaking, and it is a useful starting point for making sense of the health of an economy. But it is not the be-all and end-all. As previously pointed out, looking solely at GDP growth as a policy raison d’être can be uninformative at best and destructive at worst.

Recognising the shortcomings of GDP, many countries in recent years have begun incorporating alternative indices into their macroeconomic planning, such as the Human Development Index (HDI), the Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) and the 232 indicators comprising the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals.

Ultimately, GDP should be considered in tandem with these and other indicators of socio-economic development that cover inequality, poverty and wealth. Only then can policymakers arrive at a more holistic picture of how the country and its people are doing.

REFSA Notes is a collection of thoughts, reflections, and ideas from our research team. They aim to provide the groundwork for further discussions, commentary, research agendas and policy recommendations.

REFSA Notes #8/2022: Deconstructing Economic Indicators: Gross Domestic Product (GDP)

By Jaideep Singh

READ FULL REPORT HERE

VIEW INFOGRAPHICS HERE

For the last few decades, Gross Domestic Product (GDP) has enjoyed a preeminent position in policymaking and national planning. Though it began life in the 1930s as an economic indicator to estimate the total value of a country’s production, GDP has transformed into a tool with considerable political leverage these days.

Indeed, the pursuit of high GDP growth has become akin to the holy grail for politicians, serving as a key performance indicator – a benchmark of ‘success’. To add to its glamour, international organisations like the World Bank use variants of GDP, including per capita measures adjusted for population size, to compare nations’ development levels.

What is often forgotten amidst all of this glorification is that GDP is not a fact of nature like gravity. Instead, it is the product of a system of accounting using a series of estimations. And as a result, it is by no means perfect. Its appropriation into politics has perpetuated even more misconceptions about the true meaning of GDP.

This note therefore aims to answer two crucial questions: what does GDP really mean and in what ways is it flawed as a metric of development?

What GDP is

Definition and measurement

GDP is the ‘total value of production’ in a country during a given period, most commonly a year. It is measured by calculating the ‘total amount spent on final goods and services’ produced in a country as follows:

GDP = C + G + I + (X-M), where

Each country’s national statistical office compiles this data from many administrative and statistical sources, including surveys of businesses and households, tax declarations as well as censuses, in line with agreed upon international standards.

The final GDP value can be expressed in nominal or purchasing power parity (PPP) terms. Nominal GDP simply gives the value of production in current market prices converted to USD to allow for international comparisons. However, such a measurement does not account for differences in cost of living or exchange rate fluctuations over time. Meanwhile, PPP GDP takes the local prices of goods and services into account to ensure that currencies are valued appropriately.

Uses of GDP

The economy is a complex machine with many moving parts – composed of industries, consumers, government and other agents – that all interact with one another in many different ways. Decision makers need a number to make sense of all the economic transactions that take place within and between the players. That is where GDP and its variants come in.

The reason for stating “and its variants” is because on its own, GDP is not a meaningful measure. Instead, it is the metrics derived from GDP, including GDP growth and GDP per capita, that are used for policymaking and planning purposes:

Indicator

Meaning and use

GDP growth

Measures the increase in GDP from one period to another. Gives policymakers an idea of where a country is headed relative to its past performance.

GDP per capita

Measures economic output per person – obtained by dividing GDP by population. Gives policymakers an idea of standard of living compared to other countries.

Gross National Income (GNI)

Measures total output by residents of a country, both domestically and abroad. This includes income earned by residents working/investing abroad and excludes income earned by foreigners inside the country. The World Bank classifies countries by income level (e.g. high income, upper-middle income, etc.) based on GNI per capita.

GDP growth

GDP growth gives policymakers an idea of which economic sectors are the most productive and therefore worth prioritising as part of the national development agenda – such as high-value added manufacturing and skilled services. The indicator also informs the government and central bank’s decisions on tax and interest rate policies: if the economy is growing below par, stimulus measures may be needed.

The relationship between GDP growth and GDP per capita is also of interest, as the next sub-section illustrates.

GDP per capita

High GDP growth and a high GDP per capita tend to be associated with increasing prosperity. From a purely arithmetic standpoint, if GDP grows faster than the population, then GDP per capita grows as well. Higher per capita output in turn is correlated with a better standard of living.

In this regard, the World Bank classifies nations by income level based on output per capita, with the threshold for high income defined as a GNI per capita of $13,205 or more. Accordingly, countries that fulfil this definition are mainly in Western Europe, North America and East Asia, regions which generally enjoy a higher life expectancy, lower absolute poverty and better educational outcomes than sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America and South Asia.

What GDP is not

A measure of standard of living

It is important to remember that correlation does not imply causation. In other words, even though GDP growth and poverty reduction are related as we saw above, it does not mean that more growth automatically leads to lower poverty. This is because GDP does not capture the distribution of income across an entire population, even in per capita terms.

GDP does not acknowledge that corruption, rent seeking behaviour and other leakages can prevent economic growth from benefitting the average citizen. On its own, GDP also fails to account for urban-rural or ethnic inequality on the back of differences in productivity, wages as well as policies.

A measure of welfare

As a gross measure, GDP is only concerned with output and not the means to achieve that output. GDP does not put a value on any destruction, whether environmental or otherwise, that happens along the way in pursuit of higher production.

Therefore, treating GDP (growth) as gospel can be dangerous because it may lead policymakers to understate the unmeasurable negative effects of growth, such as pollution and loss of biodiversity.

Economist Frédéric Bastiat illustrated this problem through the ‘parable of the broken window’. In essence, if a household’s window is broken and a repairperson is hired to restore the window to its initial state, the household is effectively increasing GDP. This is because the broken window is an income opportunity for the repairperson, who would in turn contribute to consumption by buying bread from the baker and so on.

But despite the gain in GDP, fixing the window is simply a maintenance cost that does not promote productivity or significant net welfare gains.

The parable highlights GDP’s inability to take opportunity cost – the hidden cost of taking one action instead of the best alternative – into account. If the window had not been broken, the money that went towards fixing the window could have been spent on more welfare-enhancing and value-adding consumption or investment. Unfortunately, GDP ignores this dimension of decision making.

A measure of wealth

To evaluate the financial health of a business, it is not enough to look at its annual profit and loss statement. The balance sheet, with its profile of assets and liabilities, is also needed to paint a better picture of what the company is worth.

Similarly, GDP only tells us the income of a country at a point in time, not its wealth or the state’s ability to manage resources – assets – over time. As the figure below shows, the composition of wealth is much broader than just what is directly produced. National income and wealth may therefore not always rise or fall concurrently.

GDP may grow in the short-run because of the exploitation of a nonrenewable resource like oil, but if the country fails to diversify its sources of income, the eventual depletion of the resource will reduce its stock of wealth.

Indeed, the World Bank found that 26 countries recorded negative wealth per capita growth between 1995 and 2018, mostly in sub-Saharan Africa. A continuation of this trend implies that future generations will be worse off in these countries, whether due to dependence on depleting commodities with fluctuating prices or lack of investment into a wealth-generating asset like human capital (through education and healthcare) or renewable natural capital.

Once again, narrowly pursuing a quick boost to GDP growth does not do a country any favours. As we have seen, GDP growth today can make a nation poorer in the future if there is no effort to promote sustainable development through the careful management of assets like human, natural and produced capital.

Conclusion

GDP has its place in policymaking, and it is a useful starting point for making sense of the health of an economy. But it is not the be-all and end-all. As previously pointed out, looking solely at GDP growth as a policy raison d’être can be uninformative at best and destructive at worst.

Recognising the shortcomings of GDP, many countries in recent years have begun incorporating alternative indices into their macroeconomic planning, such as the Human Development Index (HDI), the Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) and the 232 indicators comprising the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals.

Ultimately, GDP should be considered in tandem with these and other indicators of socio-economic development that cover inequality, poverty and wealth. Only then can policymakers arrive at a more holistic picture of how the country and its people are doing.

READ FULL REPORT HERE

VIEW INFOGRAPHICS HERE

About REFSA Notes

REFSA Notes is a collection of thoughts, reflections, and ideas from our research team. They aim to provide the groundwork for further discussions, commentary, research agendas and policy recommendations.

RESEARCH

PILLARS

RESEARCH

CATEGORIES